Lecture: Behn's Oroonoko: ethnography, romance and history

As a Restoration playwright, poet and novelist, Behn is

Sequential four part division of the narrative of Oroonoko: the Royal Slave:

| I: Narrator's Introduction to Surinam-its people and land, 75-77 | II: Flashback to Coramantien: for origins of Oroonoko and Imoinda, 77-106 | III: Oroonoko meets Trefly, the narrator, and is reunited with Imoinda: peace & adventures, 106-125 | IV: Oroonoko leads slave rebellion, 125-141. |

Symbolic geography of the novel:

Surinam:

76: "They are extreme modest and bashful, very shy, and nice of being touched. And though they are all thus naked, if one lives forever among 'em there is not to be seen an undecent action, or glance: and being continually used to see one another so unadorned, so like our first parents before the Fall, it seems as if they had no wishes, there being nothing to heighten curiosity; but all you can see, you see at once, and every moment see; and where there is no novelty, there can be no curiosity.'

Features of the account of Surinam:

In the "contact zone" between cultures, we also get a counter-ethnography by the natives of the European:

77: "They once made mourning and fasting for the death of the English Governor, who had given his hand to come on such a day to 'em, and neither came nor sent; believing, when a man's word was past, nothing but death could or should prevent his keeping it: and when they saw he was not dead, they asked him what name they had for a man who promised a thing he did not do. The Governor told them, such a man was a liar, which was a word of infamy to a gentleman. Then one of 'em replied, 'Governor, you are a liar, and guilty of that infamy.'''

Carmantien:

83: "…Contrary to the customs of his country, he made her vows she should be the only woman he would possess while he lived; that no age or wrinkles should incline him to change, for her soul would be always fine, and always young; and he should have an eternal idea in his mind of the charms she now bore, and should look into his heart for that idea, when he could find it no longer in her face."

Thus, Carmantien is a place of romance: so this novel Oroonoko is a romance adventure centered upon its hero, Oroonoko

England:

75: Behn's statement of purpose: "I do not pretend, in giving you the history of this Royal Slave, to entertain my reader with adventures of a feigned hero, whose life and fortunes fancy may manage at the poet's pleasure; nor in relating the truth, design to adorn it with any accidents but such as arrived in earnest to him: and [this history] shall come simply into the world, recommended by its own proper merits and natural intrigues; there being enough of reality to support it, and to render it diverting, without the addition of invention. I was myself an eye-witness to a great part of what you will find here set down; and what I could not be witness of, I received from the mouth of the chief actor in this history, the hero himself, who gave us the whole transactions of his youth…"

Third discourse in the text: narrator is the teller of "a true history": but she must balance role of historian against the fact that she is also English, and one of the English settlers of Surinam: thus the narrator is a participant observer

Summary: Symbolic geography of novel:

| England = 'same,' 'enlightened' and corrupt, and the culture we know; | Coramantien has some of the innocence of nature along with the elaborate cultural forms of Europe; it practices the old social forms of romance--honor, virtue-- Europe has lost. From here the hero comes. | Surinam is 'other' and primitive and in tune with nature: it allows a glimpse of original human nature |

Oroonoko can be the hero because he can reconcile both European culture and primitive nature.

What kind of hero is he? Why are vows so important to Oroonoko?

Scene after Oroonoko is betrayed into slavery:

103-104: "[The Captain promises he will] set both him and his friends ashore on the next land they should touch at; and of this the messenger gave him his oath, provided he would resolve to live. And Oroonoko, whose honor was such as he never had violated a word in his life himself, much less a solemn asseveration, believed in an instant what this man said; but replied, he expected, for a confirmation of this, to have his shameful fetters dismissed. This demand was carried to the captain; who returned him answer that the offense had been so great which he had put upon the prince that he durst not trust him with liberty while he remained in the ship, for fear lest by a valor natural to him, and a revenge that would animate that valor, he might commit some outrage fatal to himself and the king his master, to whom this vessel did belong. To this Oroonoko replied, he would engage his honor to behave himself in all friendly order and manner, and obey the command of the captain, as he was lord of the king's vessel and general of those men under his command.

This was delivered to the still doubting captain, who could not resolve to trust a heathen, he said, upon his parole, a man that had no sense or notion of the God that he worshiped. Oroonoko then replied, he was very sorry to hear that the captain pretended to the knowledge and worship of any gods, who had taught him no better principles than not to credit as he would be credited. But they told him, the difference of their faith occasioned that distrust: for the captain had protested to him upon the word of a Christian, and sworn in the name of a great God; which if he should violate, he would expect eternal torment in the world to come. "Is that all the obligation he has to be just to his oath?" replied Oroonoko. "Let him know, I swear by my honor; which to violate would not only render me contemptible and despised by all brave and honest men, and so give myself perpetual pain, but it would be eternally offending and displeasing all mankind; harming, betraying, circumventing, and outraging all men. But punishments hereafter are suffered by one's self; and the world takes no cognizance whether this God have revenged 'em, or not, 'tis done so secretly, and deferred so long: while the man of no honor suffers every moment the scorn and contempt of the honester world, and dies every day ignominiously in his fame, which is more valuable than life. I speak not this to move belief, but to show you how you mistake, when you imagine that he who will violate his honor will keep his word with his gods." So, turning from him with a disdainful smile, he refused to answer him, when he urged him to know what answer he should carry back to his captain; so that he departed without saying any more.

Lecture 2: Dealing with Difference

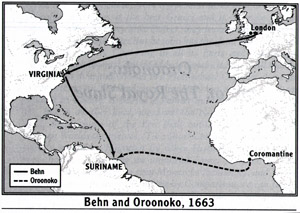

Components of the "triangle trade":

Triangle trade:

European goods to Africa for slaves to Caribbean for sugar and tobacco production to Europe [$$$]

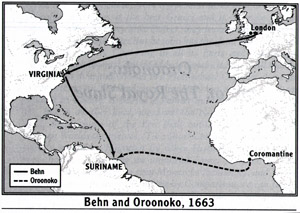

Behn's and Oroonoko's journey to Surinam

:

The transport of lives

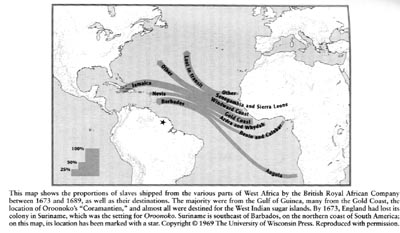

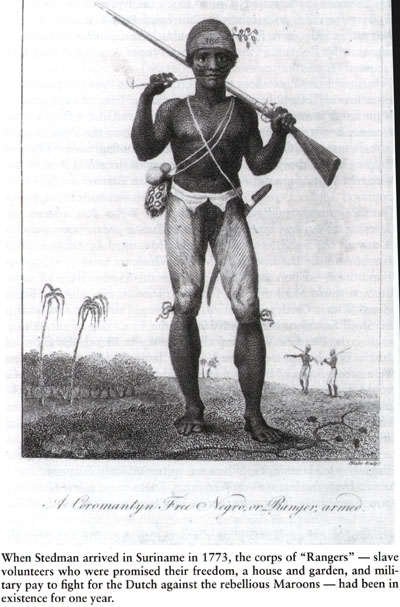

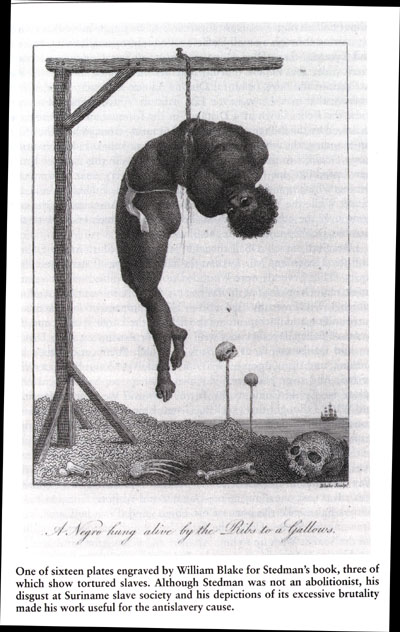

John Steadman, from Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, 1796. Frontpiece of the narrative.

"From different Parents, different Climes we came

At different periods; fate still rules the same.

Unhappy youth while bleeding on the ground;

Twas yours to fall--but Mine to feel the wound."

"A Carmantien free negro; or Ranger armed"

"A negro hung alive by the ribs from the gallows."

| Oroonoko betrayed by the English captain into slavery: |

|

"The same treachery was used to all the rest; and all in one instant, in several places of the ship, were lashed fast in irons, and betrayed to slavery. That great design over, they set all hands to work to hoist sail; and with as treacherous as fair a wind they made from the shore with this innocent and glorious prize, who thought of nothing less than such an entertainment. Some have commended this act, as brave in the captain; but I will spare my sense of it, and leave it to my reader to judge as he pleases."(P. 102) |

Is Behn's narrator anti- or pro-slavery?

|

Pacifying Oroonoko: The complex double role of Behn's narrator as participant observer [special relationship of narrator and Oroonoko; narrator's intervention to pacify Oroonoko; Oroonoko's independence] |

| 113-114: They fed him from day to day with promises, and delayed him till the Lord-Governor should come; so that he began to suspect them of falsehood, and that they would delay him till the time of his wife's delivery, and make a slave of that too: for all the breed is theirs to whom the parents belong. This thought made him very uneasy, and his sullenness gave them some jealousies of him; so that I was obliged, by some persons who feared a mutiny (which is very fatal sometimes in those colonies that abound so with slaves, that they exceed the whites in vast numbers), to discourse with Caesar, and to give him all the satisfaction I possibly could. They knew he and Clemene were scarce an hour in a day from my lodgings; that they eat with me, and that I obliged 'em in all things I was capable of. I entertained them with the loves of the Romans, and great me, which charmed him to my company; and her, with teaching her all the pretty works that I was mistress of, and telling her stories of nuns, and endeavoring to bring her to the knowledge of the true God: but of all discourses, Caesar liked that the worst, and would never be reconciled to our notions of the Trinity, of which he ever made a jest; it was a riddle, he said, would turn his brain to conceive, and one could not make him understand what faith was. However, these conversations failed not altogether so well to divert him that he liked the company of us women much above the men, for he could not drink, and he is but an ill companion in that country that cannot. So that obliging him to love us very well, we had all the liberty of speech with him, especially myself, whom he called his Great Mistress; and indeed my word would go a great way with him. For these reasons I had opportunity to take notice to him that he was not well pleased of late, as he used to be; was more retired and thoughtful; and told him, 'I took it ill he should suspect we would break our words with him,' and not permit both him and Clemene to return to his own kingdom, which was not so long a way but when he was once on his voyage he would quickly arrive there. He made me some answers that showed a doubt in him, which made me ask 'what advantage it would be to doubt. It would but give us a fear of him, and possibly compel us to treat him so as I should be very loth to behold: that is, it might occasion his confinement.' Perhaps this was not so luckily spoke of me, for I perceived he resented that word, which I strove to soften again in vain. However, he assured me that, 'whatsoever resolutions he should take, he would act nothing upon the white people; and as for myself, and those upon that plantation where he was, he would sooner forfeit his eternal liberty, and life itself, than lift his hand against his greatest enemy on that place.' |

Why doesn't the narrator act to soften the brutal treatment of Oroonoko/Caesar?

| The narrator's alibi (from the Latin, "elsewhere") |

| 132: "You must know, that when the news was brought on Monday morning, that Caesar had betaken himself to the woods, and carried with him all the Negroes, we were possessed with extreme fear, which no persuasions could dissipate, that he would come down and cut all our throats. This apprehansion made all the females of us fly down the river, to be secured, and while we were away, they acted this cruelty." |

Oroonoko's beauty:

|

How can Oroonoko be both beautiful and yet black? The narrator's complex negotitaiton with racist stereo-types |

|

80-81: "He was pretty tall, but of a shape the most exact that can be fancied: the most famous statuary could not form the figure of a man more admirably turned from head to foot. His face was not of that brown rusty black which most of that nation are, but of perfect ebony, or polished jet. His eyes were the most awful that could be seen, and very piercing; the white of 'em being like snow, as were his teeth. His nose was rising and Roman, instead of African and flat. His mouth the finest shaped that could be seen; far from those great turned lips which are so natural to the rest of the negroes. The whole proportion and air of his face was so nobly and exactly formed that, bating his color, there could be nothing in nature more beautiful, agreeable, and handsome. There was no one grace wanting that bears the standard of true beauty. His hair came down to his shoulders, by the aids of art, which was by pulling it out with a quill, and keeping it combed; of which he took particular care." |

|

88: Blushing in Imoinda's presence at the court of Oroonoko's Grandfather King: "…his (Oroonoko's) change of countenance, had betrayed him, had the king chanced to look that way. And I have observed, 'tis a very great error in those who laugh when one says, "A negro can change color": for I have seen 'em as frequently blush, and look pale, and that as visibly as ever I saw in the most beautiful white."

|

Lecture 3:Lecture three: the European in the eye of the other culture; or, seeing from Oroonoko's perspective

Problems with the Eurocentric perspective:

First paradox: while Oroonoko's greatness seems to challenge Western racist presumptions of superiority, the more that Oroonoko is both utterly unique and "just like us", the less his nobility overcomes the Western presumption of superiority.

Second paradox: while Oroonoko's profound humanity seems to offer a critique of the institution of slavery that destroys him, his radical uniqueness and superiority could justify the continued use of slavery against Africans less great than he.

The lesson: Acknowledging the radical (fundamental)

alterity (otherness and difference) of another culture is hard to do.

Here is

an example. In the tragic climax of Thomas Southerne's 1695 stage version of

Behn's Oroonoko Imoinda is about to receive a dagger in the heart from

her beloved Oroonoko, played by Mr. Savigny. But how doe they look? Oroonoko

is an English gentleman in blackface, and Imoinda is a refined white European.

This is how, in this 1759 production, white Europeans showed sympathy for African

slaves.

Here is

an example. In the tragic climax of Thomas Southerne's 1695 stage version of

Behn's Oroonoko Imoinda is about to receive a dagger in the heart from

her beloved Oroonoko, played by Mr. Savigny. But how doe they look? Oroonoko

is an English gentleman in blackface, and Imoinda is a refined white European.

This is how, in this 1759 production, white Europeans showed sympathy for African

slaves.

Can we recover some fragments of the radical alterity of the other culture from Behn's text?

| The drama of encounter in the contact zone between two alien cultures (the English and the Carib Indians) | |

|

121-122: "...we, who had a mind to surprise 'em, by making them see something they never had seen (that is, white people), resolved only myself, my brother, and woman should go: so Caesar, the fisherman, and the rest, hiding behind some thick reeds and flowers that grew in the banks, let us pass on towards the town, which was on the bank of the river all along. A little distant from the houses, or huts, we saw some dancing, others busied in fetching and carrying of water from the river. They had no sooner spied us but they set up a loud cry, that frighted us at first; we thought it had been for those that should kill us, but it seems it was of wonder and amazement. They were all naked; and we were dressed, so as is most commode for the hot countries, very glittering and rich; so that we appeared extremely fine: my own hair was cut short, and I had a taffety cap, with black feathers on my head; my brother was in a stuff-suit, with silver loops and buttons, and abundance of green ribbon. This was all infinitely surprising to them; and because we saw them stand still till we approached 'em, we took heart and advanced, came up to 'em, and offered 'em our hands; which they took, and looked on us round about, calling still for more company; who came swarming out, all wondering, and crying out Tepeeme: taking their hair up in their hands, and spreading it wide to those they called out to; as if they would say (as indeed it signified), Numberless wonders, or not to be recounted, no more than to number the hair of their heads. By degrees they grew more bold, and from gazing upon us round, they touched us, laying their hands upon all the features of our faces, feeling our breasts and arms, taking up one petticoat, then wondering to see another; admiring our shoes and stockings, but more our garters, which we gave 'em, and they tied about their legs, being laced with silver lace at the ends; for they much esteem any shining things. ...when they saw him, therefore, they set up a new joy, and cried in their language, Oh! here's our Tiguamy, and we shall now know whether those things can speak. So advancing to him, some of 'em gave him their hands, and cried, Amora Tiguamy; which is as much as, How do you do? or, Welcome, Friend: and all, with one din, began to gabble to him, and asked if we had sense and wit? If we could talk of affairs of life and war, as they could do? If we could hunt, swim, and do a thousand things they use? He answered 'em, we could. [to communal feast] ... When we had eat, my brother and I took out our flutes, and played to 'em, which gave 'em new wonder; and I soon perceived, by an admiration that is natural to these people, and by the extreme ignorance and simplicity of 'em, it were not difficult to establish any unknown or extravagant religion among them, and to impose any notions or fictions upon 'em. For seeing a kinsman of mine set some paper on fire with a burning-glass, a trick they had never before seen, they were like to have adored him for a god, and begged he would give 'em the characters or figures of his name, that they might oppose it against winds and storms: which he did, and they held it up in those seasons, and fancied it had a charm to conquer them, and kept it like a holy relic. They are very superstitious, and called him the great Peeie, that is, Prophet. They showed us their Indian Peeie, a youth of about sixteen years old, as handsome as Nature could make a man. They consecrate a beautiful youth from his infancy, and all arts are used to complete him in the finest manner, both in beauty and shape. He is bred to all the little arts and cunning they are capable of; to all the legerdemain tricks and sleight-of-hand, whereby he imposes upon the rabble; and is both a doctor in physic and divinity: and by these tricks makes the sick believe he sometimes eases their pains, by drawing from the afflicted part little serpents, or odd flies, or worms, or any strange thing; and though they have besides undoubted good remedies for almost all their diseases, they cure the patient more by fancy than by medicines, and make themselves feared, loved, and reverenced. ...[Of the warrior captains:] For my part, I took 'em for hobgoblins, or fiends, rather than men: but however their shapes appeared, their souls were very humane and noble; but some wanted their noses, some their lips, some both noses and lips, some their ears, ...

|

staging the encounter from a standpoint of greater knowledge, power, and control |

| the self-complete scene of the other world (an establishing shot) | |

| the startling moment of beholding the other = maximum of uncertainty [the non-literate society does not have the fore-knowledge available to Behn's narrator and Oroonoko] | |

| the profound anti-thesis of them and us: the naked who are curious and the dressed who are proud and self-complaisant about their sartorial capital | |

| this is a "drama of reciprocity" of apparently equal exchange (e.g. pow-wow; communal meal; etc.); however, it is the the European subjects who initiate and control the scene | |

| a simple gift causes wonder : this is a token of the naivete of the native | |

| the curiosity of the Other about the European self: here is the moment for the maximum credit given the other peoples, for they ask a question that we could imagine asking of them; they look upon us as another species | |

|

the enlightenment analysis of the gullibility of the native: this establishes the superiority and wisdom of the European perspective |

|

|

the "objective" ethnographic analysis of the way this combination of medicine and divinity achieves success: this mode of analysis removes the European subject from any proximity with the native; it looks upon the Other culture as a fascinating but inferior cultural system |

|

| the other culture is also violent, uncivilized, monstrous: this may justify the violence directed against it | |

| Indian resistance to the European intrusions: Narrator's "flash forward" to the Indian massacre of Europeans a few years later: |

|

About this time we were in many mortal fears about some disputes the English had with the Indians; so that we could scarce trust ourselves, without great numbers, to go to any Indian towns or place where they they abode, for fear they should fall upon us, as they did immediately after my coming away; and the place being in the possession of the Dutch, they used them not so civilly as the English: so that they cut in pieces all they could take, getting into houses, and hanging up the mother and all her children about her; and cut a footman, I left behind me, all in joints, and nailed him to trees. |

What if Oroonoko had written this novel? How would he narrate events and characterize English culture? Looking at his words are reported by Behn:

| 106: "Farewell, Sir, 'tis worth my sufferings to gain so true a knowledge both of you and of your gods by whom you swear." And desiring those that held him to forbear their pains, and telling 'em he would make no resistance, he cried, "Come, my fellow-slaves, let us descend, and see if we can meet with more honor and honesty in the next world we shall touch upon." |

| 125-126: "Ceasar...made a harangue to them of the miseries, and ignominies of slavery; counting up all their toils and sufferings, under such loads, burdens, and drudgeries as were fitter for beasts than men; senseless brutes, than human souls. He told 'em, it was not for days, months, or years, but for eternity; there was no end to be of their misfortunes: they suffered not like men who might find a glory and fortitude in oppression; but like dogs, that loved the whip and bell, and fawned the more they were beaten: that they had lost the divine quality of men, and were become insensible asses, fit only to bear: nay, worse; an ass, or dog, or horse, having done his duty could lie down in retreat, and rise to work again, and while he did his duty, endured no stripes; but men, villainous, senseless men, such as they, toiled on all the tedious week till Black Friday: and then, whether they worked or not, whether they were faulty or meriting, they, promiscuously, the innocent with the guilty, suffered the infamous whip, the sordid stripes, from their fellow-slaves, till their blood trickled from all parts of their body; blood, whose every drop ought to be revenged with a life of some of those tyrants that impose it. "And why," said he, "my dear friends and fellow-sufferers, should we be slaves to an unknown people? Have they vanquished us nobly in fight? Have they won us in honorable battle? And are we by the chance of war become their slaves? This would not anger a noble heart; this would not animate a soldiers soul: no, but we are bought and sold like apes or monkeys, to be the sport of women, fools, and cowards; |

| 130: "there was no faith in the white men, or the gods they adored; who instructed them in principles so false that honest men could not live amongst them; though no people professed so much, none performed so little: that he knew what he had to do when he dealt with men of honor, but with them a man ought to be eternally on his guard, and never to eat and drink with Christians, without his weapon of defense in his hand; and, for his own security, never to credit one word they spoke." |

| 135: "He considered, if he should do this deed, and die either in the attempt or after it, he left his lovely Imoinda a prey, or at best a slave to the enraged multitude; his great heart could not endure that thought. "Perhaps," said he, "she may be first ravaged by every brute; exposed first to their nasty lusts, and then a shameful death." No, he could not live a moment under that apprehension, too insupportable to be borne. ...[so] he first resolved on a deed that (however horrid it first appeared to us all) when we had heard his reasons, we thought it brave and just." |

| 140 "...and causing him to be tied to it, and a great fire made before him, he told him he should die like a dog, as he was. Caesar replied, this was the first piece of bravery that ever Banister did, and he never spoke sense till he pronounced that word; and, if he would keep it, he would declare, in the other world, that he was the only man, of all the whites, that ever he heard speak truth." |

Does the text of Oroonoko carry the words, ideas and perspectives of another culture (African, Indian); or does it merely project European ideas upon the body of Africans and Indians?

| Narrator's final word: is the story a form of symbolic reparation for the guilt she feels at being implicated in Oroonoko's death? |

|

140-141: Thus died this great man, worthy of a better fate, and a more sublime wit than mine to write his praise: yet, I hope, the reputation of my pen is considerable enough to make his glorious name to survive all the ages, with that of the brave, the beautiful, and the constant Imoinda.

|